by Jimm Budd

by Jimm Budd

An occasional spider on the wall seldom distresses guests at any of the ecotourism lodges that have opened recently along the Southern Frontier Highway in Chiapas. Most of these guests are Europeans who have come to savor the exotic and probably prefer spiders to scorpions. Spiders, after all, dine on flies and mosquitoes.

The Southern Frontier Highway (Route 307) is something of a misnomer, at least as long as it follows the Rio Usumacinta. Beyond, Guatemala lies to the east.

The road, which once ended at Palenque, now skirts the edge of the Selva Lacandona and the Bonampak archeological site. The ruins at Yaxchilan can be reached only by taking a boat along the river.

Adding to the sense of adventure are occasional signs telling motorists they are traveling through Zapatista territory. The many military checkpoints would seem to refute this. The soldiers have their own signs apologizing for any inconvenience, explaining that they are looking for illegal narcotics, weapons and immigrants.

Tourism vehicles – those with special federal license plates – usually are waived through without needing to stop. The highway must be the most protected in all of

The only delays are caused by topes, which seem to be located every few kilometers, often unpainted and unsigned. Driverguides know where to expect them. One hears how the indigenous folk, supposedly so attached to their ancestral lands, have built new communities along either side of the highway and then, unhappy about all the traffic, laid down the topes to enforce speed limits. No one can fault them for that, but apparently no authority dares to insist that they warn motorists of where the topes exist. The local folk are touchy.

The only delays are caused by topes, which seem to be located every few kilometers, often unpainted and unsigned. Driverguides know where to expect them. One hears how the indigenous folk, supposedly so attached to their ancestral lands, have built new communities along either side of the highway and then, unhappy about all the traffic, laid down the topes to enforce speed limits. No one can fault them for that, but apparently no authority dares to insist that they warn motorists of where the topes exist. The local folk are touchy.

So touchy, in fact, that Pemex stays away. Every new village has halfan dozen small businesses offering gasoline for sale at a high price. A legitimate fueling facility, were it to be built, might be destroyed.

Some communities go so far as to charge tolls to those hoping to reach tourism attractions. The road to Las Cascadas de Agua Azul near Palenque passes though two ejidos, and each collects a fee for the right of passage. Few people object. Sadly, however, tour operators have been boycotting Bonampak, where the Lacondones charge 70 pesos, a price that includes transportation to the site.

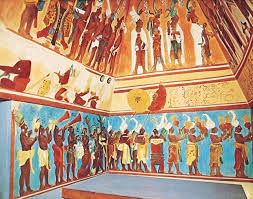

Considering that their forefathers created the pyramid, the temples and the paintings within, this assessment hardly seems outrageous. What is outrageous is cheating tourists out of a visit to the most remarkable of all the ancient Maya centers.

Happily, the Lacondones fare better with their Campamiento Rio Lacanja, with its cabins in the jungle, hiking trails and riverrafting expeditions. The accommodations are rather basic, but the better cabins come with a private bathroom and plenty of hot water. Connection with the outside world is maintained by satellite Other options include Valle Escondido near Palenque, Las Guacamayas –so deep in the jungle I never got there – and Escudo Jaguar, near the shore of the Usumacinta and the docks from which boats depart for the ruins at Yaxchilan. With the exception of Palenque and Bonampak, the ancient Maya sites are much the same to my untrained eye, but the boat ride along the river, with Guatemala just meters away, struck me as the height of adventure. Soft adventure, the kind I like. Getting to the ruins at Piedras Negras on the far shore of the river can be dangerous, I was told. But for anyone willing to risk the swirling waters, there are boatmen ready to make All this eventually leads to San Cristobal de las Casas, its historic center buzzing with a lively cafe scene, a thriving pedestrian shopping and dining strip and a number of elegant hotels in colonial mansions. The city still attracts its share of backpackers, bohemians and revolutionary wannabes, but increasing numbers of older, affluent travelers also come to take in the city's colonial architecture, rugged mountain setting and traditional Maya culture. San Cristóbal is a great walking city.

Its gentle hills, compact center, grid layout and cool climate make getting around on foot an easy pleasure, rewarding the visitor with startling new mountain vistas around each corner.

Its gentle hills, compact center, grid layout and cool climate make getting around on foot an easy pleasure, rewarding the visitor with startling new mountain vistas around each corner.

The town is in no danger of losing the feel of a Spanish colonial outpost deep in the heart of foreign territory. Although the city is officially 35 percent indigenous, that figure is misleadingly low. The surrounding mountains are dotted with dozens of Maya villages for which San Cristóbal is the main trading center. So across the graceful colonial squares and arcades, under the castiron balconies and ocherand- rustcolored churches, passes a constant pageant of women in intricately woven scarlet and indigo shawls, men in ribbon sombreros and floral tunics and girls in blue satin blouses and long black braids tied together in back with colored yarn.

Nearby is San Juan Chamula which provides mindboggling window into the spiritual side of the local culture. Ostensibly Catholic (although no ordained priest has been allowed to say mass there since 1968), the dark, candlelit church is far closer to its animistic pagan roots than to anything ever conjured by Rome. Copal burned in pumice censers and knots of worshipers sat on a pineneedlecovered floor surrounded by sacramental objects eggs, pox (a homemade cane and pineapple liquor pronounced posh), a gutted sacrificial chicken or two and bottles of Coca- Cola. Curanderos, traditional healers, rub the eggs and chickens on the infirm to draw out illness. Coke produces burps, which are believed to expel evil spirits.

Surrounding the church and an adjoining former monastery is an informal market where artisans from nearby villages sell their wares. The steps and plazas are piled high with woven belts, blankets and tablecloths, embroidered peasant blouses, leather belts and briefcases, and handmade jewelry. The quality ranges from cheap to masterful, and prices, after the requisite bargaining, from cheap to reasonable.

Even among the poorest farmers here, presentation is paramount. Figs, plums, guayabas, limes and tejocotes are arranged in perfect pyramids in plastic buckets.

Mounds of mangoes and piles of green beans fill wide straw baskets. Chilies, dried and fresh, crown conical brown ceramic bowls. Buckets of longstemmed calla lilies, birds of paradise and roses line the shelves of flower stalls. The chickens are live, their feet tied together with plastic twine so a shopper can simply slip her arm between the legs and carry the occasionally flapping bird upsidedown next to her shopping bag.